Related to beans, chickpeas, and peanuts, lentils are the edible seeds of the lens ensculenta plant, known as عدس (ʿadas) in Arabic. This legume, though small in size, is brimming with protein, providing it with great potential to feed mass populations. Historically, its combined nutritional value and affordability made for an excellent source of nourishment accessible among all social classes.

And although lentils are certainly not the most domineering of plants—typically only twelve to twenty inches in height—their roots run deep.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 2.

Origins

Lentils were among the first crops to be domesticated by man and have been cultivated for longer than any other legume. Some of their earliest instances of consumption, however, predated cultivation, and can be traced to the Syrians harvesting wild lentils between 9000 and 8000 BC (Cumo 197). During this time, lentils became increasingly significant among nomadic peoples in the Fertile Crescent. As a hardy crop that could grow on marginal land and provide yields in the spring when other food was scarce, lentils accommodated the nomadic lifestyle and provided an excellent source of protein (Cumo 197).

With consumption of lentils in the Fertile Crescent expanding, people began progressing toward lentil cultivation during a series of innovations in plant and animal utilization that facilitated a shift to early farming (Shepperson). Many of these innovations, including lentil domestication, originated near Gurga Chiya in the region of northern Iraq and north eastern Syria, around 7000 BC (Shepperson). In subsequent years, growth of lentils spread outward to Egypt, Ethiopia, Turkey, and beyond. As their cultivation proliferated, lentils provided a surplus of calories that, by feeding an expanding population, fueled urbanization and growth of civilizations in these regions (Cumo 198).

However, in later years—the Middle Ages specifically—several Arab physicians theorized that lentils caused depression, visual impairments, and stomach inflammation, deteriorating the public’s favorable view toward lentils (Cumo 200). Consequently, lentils did not play a significant role in the cuisine of this period, with few lentil recipes in cookbooks from the Medieval Arab world. Nonetheless, with the turn of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, a positive view of lentils began to reemerge; people started to more fully realize the nutritional value and healthful benefits of the lentil (Cumo 200). Today, although many Arab nations are not leading exporters of lentils, this legume still remains a common staple of daily life in the Arab world.

Cultivation

Fig. 3.

Lentils are a winter crop typically grown in the fall and harvested in the spring or summer (Alihan and Shtaya 57). In terms of climate and soil features, they are some of the less selective legumes, as their hardy nature allows them to adapt to a wide range of soil types (Alihan and Shtaya 57). Furthermore, due to their ability to tolerate periods of drought, lentils thrive in semi-arid, Mediterranean environments.

Since early cultivation, farmers have understood that lentils enrich the soil (Cumo 198). Today, we are now aware that this is a result of nitrogen fixation, by which the lentil plant converts atmospheric nitrogen into more reactive nitrogen compounds. This organic process frees farmers from using nitrogen fertilizers and increases the efficiency of the soil (Alihan and Shtaya 57).

A wide variety of lentils are cultivated, with each kind unique in texture and flavor.

Fig. 4.

Brown lentils, which are the most common of all the varieties, have an earthy, peppery flavor. They generally become soft after about thirty to forty minutes of cooking, but still retain their shape (Bachari).

Fig. 5.

Green lentils are slightly smaller than brown lentils. They tend to retain texture and taste better when cooked, and their flavor is more robust (Bachari).

Fig. 6.

Red lentils, conversely, are softer, and typically do not retain their shaped when cooked. This makes them a perfect thickening agent in soups or purees (Bachari).

These are only a few of the many varieties of lentils, but each demonstrates the versatility and diversity of this staple crop.

Healthful Benefits

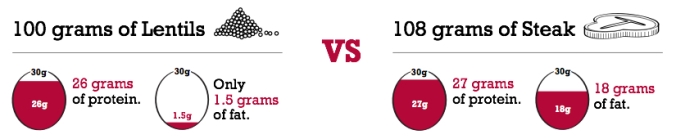

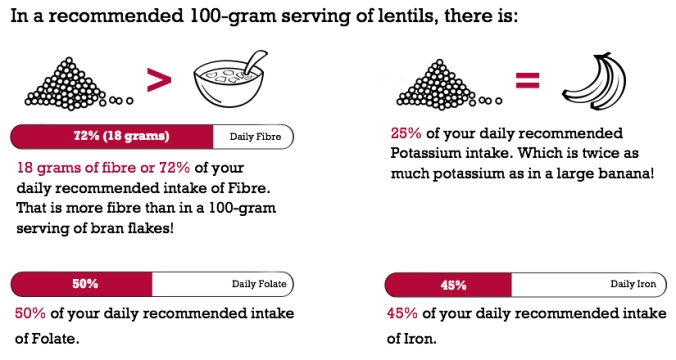

Lentils contain one of the highest amounts of protein among plants (“11 Interesting Benefits of Lentils”), and, when paired with grains, supply all essential amino acids (Cumo 198). This quality is crucial, as lentils and grains provide an inexpensive means of consuming an adequate diet–especially to those for whom meat and fish are unattainable. In addition to massive amounts of protein, lentils are also a good source of fiber, folate, copper, manganese, iron, phosphorous, vitamin B1, and potassium (“11 Interesting Benefits of Lentils”).

These nutrients, as well as other components of the lentil, aid in digestion, promote a healthy heart, provide amino acids necessary for muscle generation, and aid in controlling blood sugar (“11 Interesting Benefits of Lentils”).

Fig. 7.

Cultural and Religious Significance

More than merely a nutritious staple, lentils have been tied to culture since ancient times, particularly in the sphere of religion.

As early as 3000 BC, a time when Egypt was a hub of lentil cultivation, Egyptians worshipped the god Horus with hopes that he would ensure a bountiful lentil harvest. Additionally, lentils symbolized resurrection in Egyptian religion and were placed in tombs as food for the journey to the afterlife (Cumo 199). Lentils persisted as an integral staple in Egyptian culture, with the legume eventually becoming vital to Egypt’s Christian community as well. Lentil dishes were heavily consumed by the Copts and other Christian sects during fasting times (Denker). In such ways, lentils became emblematic of Egyptian identity.

Lentils were also esteemed among Hebrews, with farmers believing the seeds were a supreme form of nourishment. And in one Biblical story, lentils were a godsend to Esau, who was so famished that he offered his birthright to his brother Jacob in exchange for a lentil porridge (Denker):

29″Once when Jacob was cooking some stew, Esau came in from the open country, famished. 30He said to Jacob, ‘Quick, let me have some of that red stew! I’m famished!’31Jacob replied, ‘First sell me your birthright.’32′Look, I am about to die,’ Esau said. ‘What good is the birthright to me?’33But Jacob said, ‘Swear to me first.’ So he swore an oath to him, selling his birthright to Jacob.34Then Jacob gave Esau some bread and some lentil stew. He ate and drank, and then got up and left.” Genesis 25:29-34

This lentil porridge was the precursor to a dish called mujaddarah (مجدرة), which mainly consists of rice and lentils topped with caramelized onions. The first recorded recipe for mujaddarah was compiled by Iraqi scholar al-Baghdadi in his cookbook Kitab al-Tabikh, 1226 AD (Lasota). Since that time, this has been a popular dish in the Middle East; in Jewish communities, particularly those of Syrian or Egyptian background, it is sometimes nicknamed “Esau’s favorite” (TartQueen’sKitchen).

Fig. 8.

Fig. 9.

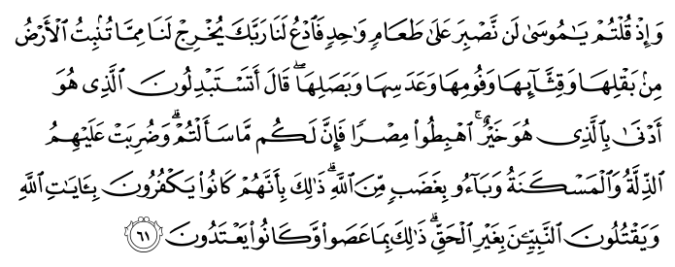

Lentils were similarly apparent in Islam, with Muslims esteeming them as a valuable food source. The Prophet specifically mentions lentils in verse (2:61) of the Quran (Surat al Baqara), which says the following:

And [recall] when you said, “O Moses, we can never endure one [kind of] food. So call upon your Lord to bring forth for us from the earth its green herbs and its cucumbers and its garlic and its lentils and its onions” (Ontology of Quranic Concepts).

Fig. 10.

Such ties to Islam are also evident in the dish Shurba al- ‘Adas (شوربة العدس). This lentil soup, popular in Palestine and the Levant, is commonly served on iftar (افطار, breaking the fast) tables during Ramadan. Its prevalence during this time of fasting indicates its value in Muslim tradition.

Fig. 11.

Even beyond religion, lentils’ enduring history and longstanding use have contributed to its deep roots in Arab culture. Lentils are referenced in in a variety of contexts, from folktales to Arabic proverbs, such as the following aphorism:

“He who knows knows, he who doesn’t know says ‘a handful of lentils'” (Brill)

In each of these areas, whether agriculture, cuisine, or even pithy sayings, lentils maintain a legacy that continues to endure.

Works Cited

“11 Interesting Benefits of Lentils.” Organic Facts, 6 Nov. 2017, http://www.organicfacts.net/health-benefits/health-benefits-of-lentils.html.

Arafat-Ray, Sahar. “Mujadarah مجدرة.” TartQueen’s Kitchen, 17 Oct. 2014, http://www.tartqueenskitchen.com/2014/10/17/mujadarah-%D9%85%D8%AC%D8%AF%D8%B1%D8%A9/.

Fig. 8; Fig. 9. Arafat-Ray, Sahar. “Mujadarah مجدرة.” TartQueen’s Kitchen, 17 Oct. 2014, http://www.tartqueenskitchen.com/2014/10/17/mujadarah-%D9%85%D8%AC%D8%AF%D8%B1%D8%A9/.

Bachari, Amadeus. “Understanding Different Types of Lentils.” AdasCan Grain Corporation, 20 June 2017, http://www.adascan.ca/blog/understanding-different-types-lentils/.

“Language and Culture in the Near East.” Edited by Shlomo Izre’el and Rina Drory, Google Books, E.J. Brill, 1995, books.google.com/books?id=majtzzdiaEEC&pg=PA235&lpg=PA235&dq=lentils%2Bin%2Barab%2Bculture&source=bl&ots=dDVnGxuTGN&sig=_eKntxoMncE1NN286qcgUbglltg&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjRqInvvLDXAhVESiYKHQ7oBasQ6AEIfDAP#v=onepage&q=lentils%20in%20arab%20culture&f=false.

Cokkizgin, Alihan, and Munqez J.Y. Shtaya. “Lentil: Origin, Cultivation Techniques, Utilization and Advances in Transformation.” Agricultural Science, vol. 1, no. 1, 2013, pp. 55–62., http://www.todayscience.org/AS/article/as.v1i1p55.pdf.

Cumo, Christopher Martin. “Foods That Changed History: How Foods Shaped Civilization from the Ancient World to the Present.” Google Books, ABC-CLIO, 30 June 2015, books.google.com/books?id=WqfACQAAQBAJ&pg=PA200&lpg=PA200&dq=lentils%2Bin%2Bthe%2Barab%2Bword&source=bl&ots=JcKio9vqPD&sig=4pUic48TA_VSI_-b_I3oKAXnMVc&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwju1IGAxa3XAhXorVQKHTSAAQAQ6AEIUDAI#v=onepage&q&f=false.

Denker, Joel. “Food in the ‘Hood.” The InTowner, InTowner Publishing Corp., 12 Nov. 2013, intowner.com/2013/11/12/the-lentil-poor-mans-meat/.

Fig. 5. “Green Lentils.” Nuts.com, 12 Apr. 2017, nuts.com/cookingbaking/beans/lentils/lentils.html.

Fig. 7. “Health & Nutrition.” Lentils.org, 30 Jan. 2017, http://www.lentils.org/health-nutrition/.

Lasota, Aleksandra. “Mujaddara According to Basel – Arabic Rice with Lentils.” The Al’s Kitchen, 21 Dec. 2015, thealskitchen.com/2015/12/21/mujaddara-according-to-basel-arabic-rice-with-lentils/.

Fig. 3. “Lentils.” The Bible Garden, Charles Stuart University, 6 Mar. 2011, http://www.csu.edu.au/special/accc/biblegarden/plants-of-the-garden/lentils.

Fig. 10. “Lentil.” Lentil – Ontology of Quranic Concepts from the Quranic Arabic Corpus, 2011, corpus.quran.com/concept.jsp?id=lentil.

“Lentil.” Lentil – Ontology of Quranic Concepts from the Quranic Arabic Corpus, 2011, corpus.quran.com/concept.jsp?id=lentil.

Fig. 4. “Lentils.” Tastycraze.com, tastycraze.com/n7-32159-Lentils.

Fig. 6. “Red Lentils.” Nuts.com, 22 Sept. 2017, nuts.com/cookingbaking/beans/lentils/lentils-red.html.

Rohana, M. “Sprouting Lentils Time Lapse.” YouTube, 15 Jan. 2015, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ILw71mDcnfw&feature=youtu.be.

Shepperson, Mary. “How Ancient Lentils Reveal the Origins of Social Inequality.” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 11 Oct. 2017, http://www.theguardian.com/science/2017/oct/11/lentils-origins-of-social-inequality.

Fig. 1. “Spicy Lentil Pasta.” Green Eatz, 29 May 2013, http://www.greeneatz.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/green-blog-spicy-lentil-pasta.gif.

Fig. 11. Wright, Clifford A, and Najwa al-Qattan. “Lentil Soup.” Recipe: Shurba Al- ‘Adas (Arab Levant) Lentil Soup, 9 Jan. 2007, http://www.cliffordawright.com/caw/recipes/display/bycountry.php/recipe_id/736/id/5/.