Coffee is synonymous with bright eyes and beautiful mornings, its warmth–and caffeine–a helpful tool when comfort and energy are necessities. In a fast-paced world, it’s no surprise that coffee consumption worldwide was at an all-time high of almost 9.08 billion kilograms per year. Specifically within the Arab World, coffee holds integral cultural and historical roles, neither of which can be understood without first tracing it back to its roots.

A Brief History

There are a variety of stories that claim to tell the true origin of coffee, or قهوة (qahwa), but most widely accepted is the tale of Kaldi. An Ethiopian goatherd, Kaldi tried a “red bean” after his goat ate one and instantly showed a noticeable change in its demeanor. Soon, a neighboring Sufi monk noticed Kaldi’s new habit of eating the beans, and, seeing their potential for increasing attentiveness for prayers, began to eat them himself. However, the monk decided to boil his and drink the liquid rather than eat the fruits whole. Thus, coffee drinking was born.

Originally grown by an Ethiopian tribe, coffee was eaten, not drunk, by the group between 575 to 850 CE. Ground coffee beans were mixed with animal fat to provide long-lasting energy, like a rudimentary protein bar. It was simultaneously being newly cultivated in Yemen beginning in 575 CE. Coffee was not brewed as a hot beverage until some time between 1000 and 1300 CE, when the physician and philosopher Avicenna of Bukhara first described the “medicinal” properties, which he coined “bunchum”, of the plant.

Coffee then spread to the great Arab cities, beginning with Mecca in 1414 and eventually reaching Medina between 1470 to 1499, then Constantinople in 1517. Despite rigorous means of protecting the secrets of its cultivation, including heating and boiling exports to ruin any possibility of their germination, coffee was eventually smuggled into India in 1600. As Europe slowly gained power and the knowledge of coffee cultivation began to permeate throughout the globe, the Arab world’s sovereign enjoyment of the plant was eventually trampled by colonial powers. Coffee was soon popular worldwide.

The Growth Cycle

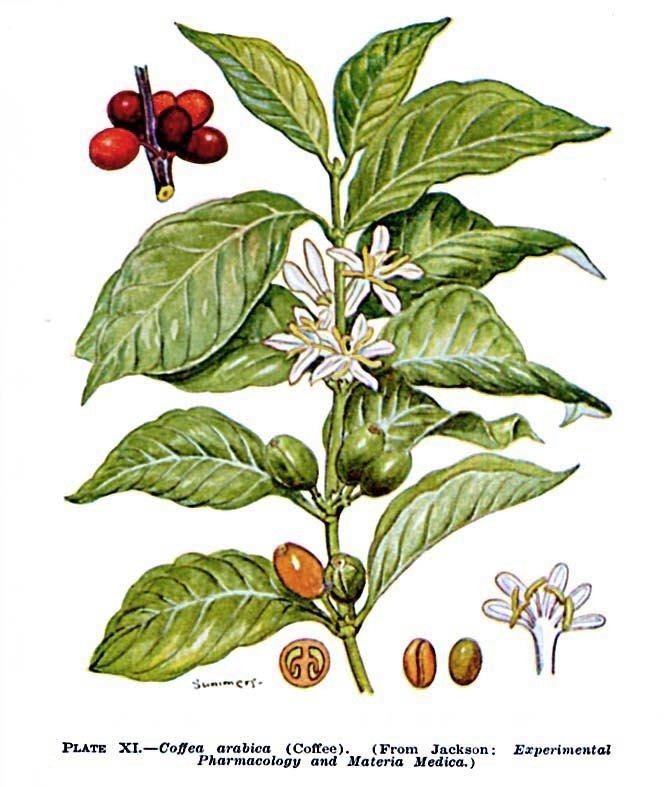

The genus Coffea is shared by over twenty different species, but only two types, Coffea arabica and Coffea canephora var. Robusta, are popular today. The arabica species is native to East African and Central and South American countries, while robusta can be traced to West Africa and Southeast Asia.

Coffea arabica (Source: Know Your Grinder)

Seven to eleven months after being planted, small, cherry-like fruits, each of which hold two coffee beans, appear on the trees. A single plant can produce up to 4,000 coffee beans annually, reaped either by hand-picking or by strip-harvesting. Beans are then processed by either the wet method (soaked in enzymatic tanks to loosen outer coatings, then dried for two weeks) or the dry method (dried in the sun for four weeks), both of which remove outer layers to get to the bean. Based on the preferred flavor or specificity, beans are then sorted by size and roasted accordingly.

See the production process of Coffea arabica in action!

Nutritional Value

Although coffee is not significantly nutritious, it does provide various micronutrients, including potassium, magnesium, and niacin. It also contains compounds, such as chlorogenic acids and melanoidins, that have antioxidant properties, meaning they help to prevent or slow cell damage.

The most notable element of coffee, however, is caffeine, a chemical that promotes mental alertness and improves sleep patterns. Typically, each cup of coffee contains 75-100 milligrams of caffeine. Such characteristics were extremely intriguing to Arabs and continue to fuel the coffee market today.

Cultural Significance

Because Islamic law discouraged–or even outlawed–drinking alcohol, coffee was seen as an enjoyable alternative, especially because of its stimulating aftereffects that were perceived as similar to those of the banned beverages. In fact, the word now used for coffee, قهوة (qahwa), originally meant wine.

- Arab Figures in a Coffee House, Carl Friedrich Heinrich, 1870. (Source: Art.com)

As its popularity grew, new gathering places for drinkers of coffee began to be constructed. These first coffeehouses appeared first in Constantinople in 1554, and they blossomed as centers for intellectualism, music, and social interaction.

However, according to religious leaders, the rising popularity of such community establishments began to detract from Muslims’ presence in mosques, causing the enraged mufti to legally forbid coffee drinking, claiming it had “wine-like” effects and led drinkers down a “path of sedition”. Thus, in 1511, all of the coffeehouses in Mecca were shut down by then-governor Khair-Beg. These legal restrictions had little lasting impact, though, for Egyptian sultans quickly reversed the ruling and reinstated coffee-drinking, encouraging the rest of the Arab world to do the same.

The sense of community that coffee inspired in the days of Constantinople still lives and breathes in the Arab world today. Such lasting cultural significance can be seen in UNESCO’s 2015 announcement of Arabic coffee as Intangible Cultural Heritage, the organization citing its strong connection to generosity and community as the sources of its long-standing strength.

In the process that UNESCO recognizes, Arabs prepare coffee in front of their guests to show them hospitality. First, beans are carefully selected, then roasted in a shallow pan, or a dallah, over a fire. After they are heated, the beans are boiled and brewed into the drink, which is then poured into smaller cups, known as finjaan. Each cup is only filled to a quarter of its fullness, and the eldest is normally served first.

A woman preparing coffee for guests (Source: UNESCO)

This process is highly ritualized, the cup and pot each needing to be held in specific hands and the number of cups one is permitted to drink being bluntly regulated (at least one, no more than three). Preservation of this tradition is ensured by its passing onto younger children, who learn through observing and assisting their parents with the process. Through traditions like this, the connectivity proliferated by the coffeehouses of Mecca, Medina, and Constantinople still remain prosperous today.

Artistic Responses

Like other elements of cultural significance, coffee has inspired a variety of poems and lyrical expression. The first known piece using the plant as its muse was written by Sheik Ansari Djezeri Hanball Abd-al-Kadir in 1587 and titled, “In Praise of Coffee”. It reads,

“Oh Coffee, you dispel the worries of the Great, you point the

way to those who have wandered from the path of knowl-

edge. Coffee is the drink of the friends of God, and of His

servants who seek wisdom.

…No one can understand the truth until he drinks of

its frothy goodness. Those who condemn coffee as causing

man harm are fools in the eyes of God.

Coffee is the common man’s gold, and like gold it brings to

every man the feeling of luxury and nobility…Take time in

your preparations of coffee and God will be with you and

bless you and your table. Where coffee is served there is grace

and splendor and friendship and happiness.

All cares vanish as the coffee cup is raised to the lips.

Coffee flows through your body as freely as your life’s blood,

refreshing all it touches: look you at the youth and vigor

of those who drink it.

Whoever tastes coffee will forever forswear the liquor of

the grape. Oh drink of God’s glory, your purity brings to man

only well-being and nobility”

Other poems, such as “Coffee Companionship”, express great love for the plant, exemplified in the following connection to Islam:

Grief is not found within its habitations. Trouble yields humbly to its power.

It is the beverage of the children of God, it is the source of health.

It is the stream in which we wash away our sorrows. It is the fire which consumes our griefs.

Whoever has once known the chafing-dish which prepares this beverage, will feel only aversion for wine and liquor from casks.

Such passionate works that coffee has inspired signify the importance within the personal and cultural connections amongst members of the Arab community.

Coffee Around the Arab World

Today, the Arab world relies heavily on imports for its coffee supply, the majority of which come from the “coffee belt”, which includes equatorial countries such as Brazil,

Egyptian coffee being prepared (Source: Bunaa)

Ecuador, and Kenya. Although consistently popular throughout the Arab world, the means in which coffee is prepared vary from country to country. In Egypt, for example, coffee is prepared with a small layer of foam, or a”face”, while in Lebanon, it lacks any foam and is instead boiled only once. In Yemen, coffee beans are mild-flavored and are combined with ground spices, like cinnamon, saffron, and cardamom. As displayed in the video below, in Saudi Arabia, green coffee beans are boiled until slightly frothy, then removed from heat and combined with cardamom and creamer.

Watch to see how Saudi coffee is made!

Just as rich in history as it is in flavor, coffee has a long-standing connection with the Arab world. Through continued appreciation of the plant itself and the traditions it has created, coffee will continue to maintain its position as the “wine of Islam” for many more cups to come.

Works Cited

“32. A History of Coffee in Literature.” Web Books, http://www.web-books.com/Classics/ON/B0/B701/37MB701.html. Accessed 23 October 2018.

“Arab Coffee, a symbol of generosity.” UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage, 2015, ich.unesco.org/en/RL/arabic-coffee-a-symbol-of-generosity-01074. Accessed 23 October 2018.

“Caffeine Content for Coffee, Tea, Soda and More.” Mayo Clinic, Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research, 14 Apr. 2017, http://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/nutrition-and-healthy-eating/in-depth/caffeine/art-20049372. Accessed 23 October 2018.

Coffee and Health, 24 Nov. 2017, http://www.coffeeandhealth.org/topic-overview/nutrition-information/. Accessed 23 October 2018.

Fridell, Gavin. Coffee. Polity Press, 2014, Cambridge.

Hugo, John. “Coffee and qahwa: How a drink for Arab mystics went global.” BBC News, 18 April 2013. https://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-22190802. Accessed 23 October 2018.

Luttinger, Nina, and Gregory Dicum. The Coffee Book: Anatomy of an Industry from Crop to the Last Drop. 2nd ed., New Press, 2006, New York.

“Middle Eastern Coffee Culture and History.” Kopi Luwak Direct, 2017, kopiluwakdirect.com/middle-east-history-culture/. Accessed Oc

Mlynxqualey. “Arabic Literature and the Politics of Coffee: 3 Books.” ArabLit, 19 June 2018, arablit.org/2018/06/21/arabic-literature-and-the-politics-of-coffee-3-books/. Accessed 23 October 2018.

“Moroccan Arabic Coffee.” Travel Exploration, 2018, travel-exploration.com/ subpage.cfm/coffee. Accessed 23 October 2018.

“The Current State of the Global Coffee Trade.” International Coffee Organization, 14 Oct. 2016, http://www.ico.org/monthly_coffee_trade_stats.asp.

Seidel, Kathleen. “Coffee–The Wine of Islam.” Serving the Guest: A Sufi Cookbook, 2000, http://www.superluminal.com/cookbook/essay_coffee.html. Accessed 23 October 2018.

“Sixth Century: Coffee Arrives on the Arabian Peninsula.” The History of Coffee and Coffeehouses. http://webpage.pace.edu/nreagin/s2004his296k/karenaleta/MiddleEast.html. Accessed 23 October 2018.

Warah, Holly S. “How to Prepare and Enjoy Arabic Coffee.” Arabic Zeal, 29 Aug. 2011, arabiczeal.com/prepare-enjoy-arabic-coffee/. Accessed 23 October 2018.